KALÉIDOSCOPE

4 July 2020 – 6 September 2020

Susan Morris, SunDial:NightWatch_Activity and Light 2010–2012 (Tilburg Version), 2014, Jacquard: cotton, linen yarn, 155 x 589 x 4 cm, Stiftung Kunsthaus-Sammlung Pasquart; Foto: Stefan Rohner

KALÉIDOSCOPE

CURRENT VIEWS ON THE 30 YEARS OF COLLECTION

4.7.–6.9.2020

Marking its 30th jubilee this year, the Kunsthaus looks back on 30 years of collecting activity. Oriented at the beginning towards regional art, the collection has focused for several years on works by international artists shown in an exhibition at the Kunsthaus. Today the Kunsthaus-Collection numbers over 1800 works.

Kaleidoscope means «seeing beautiful forms», but its play with forms goes beyond its meaning: the Kaleidoscope inspires us to reflect on other perspectives. It combines fragments in new forms and produces a multiplicity of different ways of seeing things that connect or recoil from each other. The exhibition presents new acquisitions, works that have rarely been seen as well as others that are familiar, series of works or individual pieces. The variety reflects the changing views of those protagonists who have helped mould the collection, but also the role of donations in defining new emphases. In this encounter between works there can emerge on the one hand relationships or correspondences; on the other hand, the individual pieces often have little in common. The testing of constellations and contemporary perspectives on the collection allow new contexts to emerge.

We feel it is important to expand our perspectives on 30 years of the collection with the work of current artists from Biel. Béatrice Gysin (*1947 in Zurich, lives and works in Biel), Katrin Hotz (*1976 in Glarus, lives and works in Biel), Jeanne Jacob (*1994 in Neuchâtel, lives and works in Biel) and Simon Ledergerber (*1977 in Brunnen, lives in Zurich and works in Biel) provide various responses to selected works from the collection. Their artistic view creates a lively dialogue with the existing work.

As a satellite project the artist Till Velten (b. 1961 in Wuppertal, Germany, lives and works in Zurich and Berlin) presents in the Collections Room of the Kunsthaus his curatorial project TAUSCHEN. A work by Till Velten.

FOYER

San Keller has developed a critical and humorous practice by making his art a part of daily life. Participative acts are his main focus. He questions ways of dealing and operating as well as the role of the artist and the place of art in society. With San Kellers Stammtisch (2007) he invites visitors to take a seat, have a drink and enter into conversation – perhaps also with the artist himself. The painter Jeanne Jacob made several new works for the exhibition, with which she in various ways reacts to artists in the collection. In the foyer she juxtaposes Party, Party (2020) with San Keller’s Stammtisch (2007). The two figures in the painting seem to be caught in a moment between fun and boredom. Jacob paints people and bodies, unstaged and caught in an everyday matter-of-factness; sensuous and intimate, without appearing pornographic. They are situated in a kind of state of uncertainty, in which ideals are subverted and contradictions are possible.

In the corridor to the foyer we find Jürg Moser’s work Lucky Strike (1997), a structure resembling a handrail made of metallic-looking graphite, with which the artist recalls a bar in New York of the same name. Moser is concerned with volumes and the experimentation with unusual materials such as tar, beeswax and graphite and their various states. With the choice of materials, he creates a sculptural vocabulary that seems simultaneously sensuous and sober. Next to this we see Pascale Wiedermann’s large-scale installation Heimlich (1996), in which a striped knitted tube crosses the space, in the end of which a monitor reproduces the journey through this same colourful stocking. Wiedermann’s works illustrate in a variety of ways emotional states and feelings; by using traditional female techniques such as knitting, embroidery and crochet and materials like wool, fabric or entire items of clothing, she makes a critical contribution with her early works to female cultural history.

PHOTOFORUM ROOMS CORRIDOR

In his work quercus (1992) herman de vries works with found pieces from nature. Whatever he collects and brings back from his walks in nature or his journeys all over the world (branches, stones, leaves, bones, earth, artefacts, shells, bark), doesn’t follow a specific system but is determined by the poetry of the moment. In this sense he is less concerned in his artistic work with a superficial aesthetic, but with the perception of nature and an inspired potential for awareness that to a certain extent is transmitted by nature. He says that being naked makes him free, open and receptive, so that he can feel himself connected to the world.

LEFT WING ROOMS PHOTOFORUM AND FACADE

The exhibition kicks off with an older generation of artists from Biel who were significantly involved in the foundation of the Kunsthaus and whose works also became part of the collection. Whereas today acquisitions from national and international artists from the exhibitions programme are the focus of the collection, at that time it was primarily local artists. Outside we are greeted by the neon sculpture merci, 1995 by susanne mueller, which at night radiates from the roof of the extension. The artist made it on the occasion of the referendum in 1995, adopted by the large majority of voters, in favour of the plans to extend the Kunsthaus. Next to it, attached to the facade of the old building are René Zäch’s 22 metal plates with triangles. These Fassadenzeichen (1990) are a signal identifying cultural buildings and institutions as places of art.

In the rooms of the Photoforum works by Walter Kohler-Chevalier, Heinz-Peter Kohler and Urs Dickerhof encounter artists’ portraits by Jeanne Chevalier. Mingling among those who accompanied the Kunsthaus in the past is the invited artist from Biel, Katrin Hotz, who responds to the Kunsthaus-Collection with various older works from her archive. Her burning tower Vergessen das Vergessen nicht (2007) enters into conversation here with Martin Ziegelmüllers 5th cycle Teilchenbeschleuniger (2013-14).

RIGHT WING ROOMS PHOTOFORUM

In the other wing we find ourselves in the video work Horizons of a World (2001) by Marie José Burki, who with her rhythmical and in part strongly zoomed shots causes an image of a landscape to form. Next to this, in herman de vries’ from white earth (1993) the landscape is depicted not as an image, but in the form of earth rubbings on paper, that join together as a minimalistic presentation of monochromes. At the centre of his practice is nature as a space of life and experience. He develops his own systems in order to preserve moments of natural variety. Simon Ledergerber has selected this work with which to juxtapose his sculpture Vor dem Gesetze (nach Kafkas Text) (2019), with which he refers to Franz Kafka’s parable of the doorkeeper. He works primarily with natural materials and is concerned with processes and questions of formation. At the heart of his work is the consideration of how to give a form to raw material, without dominating its features, but rather incorporating that which is already inherent in the material. In this way, his works are often situated in the field of tension between nature and artificiality.

PASSAGE GALLERIES

On entering the galleries we are confronted in the passage by Stefan Banz’ humorous and self-reflective work Laugh. I nearly died (2005). This consists of a trailer, sawn through the middle to allow a glimpse of the inside and the artist’s photographs and paintings, damaged in a destructive act. The title becomes a metaphor: what should be done with works an artist has made and assembled over years – re-work, destroy or dispose of them or will they have cultural significance in the future?

GALLERY 1

In Gallery 1 we encounter Airport (1990), Peter Fischli’s and David Weiss’ prosaic photographs of airports. They are from a group of photos of tourist attractions, green spaces or, as here, unwanted travel stops. The landscape dominated by machines as a postcard motif, as it were. Unpopular as transit places, they are associated with the loss of time. Markus Raetz’ Form im Raum (1991/92) contrasts the immediate legibility of a familiar symbol with the process of perception. At the centre is the experience of the dynamic and continuous transformation of image and dissolution, order and chaos, figuration and abstraction, or space and surface. By circling round the sculpture and continually changing our viewpoint, we find or select in this fluid form a familiar icon of media culture: Mickey Mouse. Through her choice of Raetz’ Form im Raum, Jeanne Jacob alters the perspective and creates an unusual relationship: by giving the icon 99 faces Fluide Mickey (2020) dissolves the idealised and stereotypical image of Mickey Mouse. The varied emotions of the mouse faces make different characteristics visible. Jacob gives the fictive character a personality and thus transforms the collective into the individual.

GALLERY 2

The investigation of temporality is the subject of the right-hand side of Gallery 2. Susan Morris’ woven, large format wall carpet SunDial:NightWatch_Activity and Light 2010-2012 (Tilburg Version) (2014) refers to the digital recordings of her sleep and wake phases which she recorded with an acti-watch for several years. Moments of little activity, recorded at night, are presented in the middle of the weaving and suggest a night sky, a dark river or a ravine within a landscape. On the one hand consistently schematic, on the other imbued with intimacy, the weavings communicate coded information concerning specific events and aspects of behaviour. In Exposure #64: N.Y.C., 555 8th Avenue, 11.26.08, 5:52 p.m. (2008) and other photographs in the series Barbara Probst splits moments and situations into various aspects of the same instant. Cameras synchronised by radio record the same subject at the same time from different viewpoints.

In the left-hand side of the room Dexter Dalwood creates on the flat, painted surface of his painting Robert Walser (2012) a breathtaking pluralism that refracts and collides the memory of the past with future recollections of the present. Many people are invoked in the titles of his works – as, in this case, Robert Walser. None of them make an appearance in the paintings themselves. Dalwood’s compositions present a structured context, an interior or exterior environment whose various elements offer a space within which these people, their actions and the ideas and events associated with and surrounding them can unfold. Leiko Ikemura reflects in her work on foreignness and disruption. Trojanischer Krieg (1986) refers to the Trojan myth, in which she found an analogy to the attack on Pearl Habour in 1941 and its aftermath. The insight into the inner necessity of going deep into oneself corresponds with the senselessness of the external war. Densely and expressively painted, the images stand for inner states that not infrequently open chasms. Both large scale works can be read as a form of contemporary history painting. They show places laden with contemporary meaning or allow the viewer glimpses into the environment of well-known figures from culture or mythology.

GALLERY 3

The last room in the Galleries combines works by Miriam Cahn, Klaudia Schifferle, Philippe Vandenberg, Joseph Beuys, Franz Wanner, Julia Steiner, Klodin Erb, Francisco Sierra and Jeanne Jacob and draws together themes of dreamworlds, fantasy, inner landscapes and surreal visual worlds. Julia Steiner’s large format gouache drawings, produced with the smallest brush, are developed in meditative concentration. Pictorial spaces flow into one another, produce dense and light, wild and gentle areas, with which she aims to interpret neither landscapes nor nature. In her figures Miriam Cahn depicts feelings she has before people, animals and plants. She also focuses here on ambivalences which don’t allow a being to be clearly assigned a gender or species. Her intensely coloured paintings are not illustrative, but always an approach to physical experiences. In this room, too, Jeanne Jacob’s Portrait mit Rosen (2020) responds to Francisco Sierra’s Die Ankunft (2007). Together the two heads create a humorous portrait gallery in which both individuals, if in very different ways, stand in painted form between the illustration of truth and absurdity. While Jacob paints intuitively and layers surfaces, forms and figures until she arrives at a result through the painting process, Sierra uses an old master palette and produces his work with great precision. Even though both figures have something repellent, they are nonetheless painted with great empathy.

PARKETT 1 CORRIDOR

For his series Arbeit der Maschinen (1991) René Zäch made a selection from hundreds of illustrations of machines and arranged them in a play of form and colour. The aesthetic of his objects, robbed of their function, becomes the focus. At the end of the passage Hervé Graumann’s sculpture Hard on Soft (1993) rocks back and forth on a large foam plinth, established by the programmed printer placed on it. Since the end of the 1980s Hervé Graumann’s work has developed parallel to computerised data technology. The artist questions, criticises, distorts and amuses himself over the means, the formal vocabulary and the specific logic of this modern technique.

PARKETT 1.1

In his video sculpture Berglandschaft (2007) Hervé Graumann examined the possibilities of digital image production. It consists of a 3D video animation, generated from a photographic image on the computer. While the images develop in the course of time, the basic information taken from a photograph is proved to no longer be sufficient. Thus one finds oneself in a room in which colour tints fill the empty spaces, pixels form geometrical patterns or the objects change size of their own accord. These visual distortions give the landscapes at the same time a real as well as an unreal character. In contrast to and in dialogue with these are the landscapes of Bruno Meier, distinguished by their rhythmical distribution in large areas of colour, clarity and toned down palette. In these meticulous constructions the painter limited himself to just a few subjects, concentrating rather on the emptiness and order in the space. Erik Steinbrecher focuses his attention on mobile architectures, such as fences, a garden shed or a tent; or his three-dimensional works take as their subject industrially produced elements from building supplies stores and modules of cheap pre-fabricated architecture that through their formal language refer to an everyday aesthetic. Through the positioning and staging of Vordach (2003), the pure form of the fence takes on a monumental character, creating a theatrical moment.

PARKETT 1.2

The three sculptures Bio Diversity (Blooming, Flying, Standing) (2018) by Florian Graf consist of the same three geometric forms – a circle, an L-form and a zigzag –, assembled in three different ways to evoke a human, a bird or a plant. This reduction and stylisation of the physical appearance of living species can be read as a metaphor for the term ‘biodiversity’. Graf examines in his work themes connected with architecture and landscape architecture and thus investigates the psychological and emotional impact of spaces on our bodies as well as on our psychological system. Produced in three different colours, they intimate a game between artificiality and naturalness. Com&Com first focused on the subject of nature in 2008 with their Postironischen Manifest and began to integrate the beautiful, the affirmative and the emotional in their work. The three branches refer to their exhibition at the Kunsthaus in 2010: a tree with all its roots was the inspiration for all these works – named natural readymades by the artists. During a performance they dissected the tree in individual parts, gave these numbers and distributed them among the audience. In this way their tree could take on a further cycle in life (after nature and art). The works hang in a dialogue with still lifes by Bruno Meier. These quiet impressions are exact observations of the quotidian. The artist stayed almost completely away from social life and lived a radical way of working, totally at odds with the tendencies of today’s art system.

PARKETT 1.3

Oriental Carpet I (2006) is a photographic version of Hervé Graumann’s Patterns, which the artist conceived on the occasion of his exhibition at the Kunsthaus. In this ornamental still life the objects are arranged according to criteria of balance, form or colour in small modules that are reproduced identically in dozens of examples. The plastic bowls, shell containers, knives, drinking straws, cassettes, washing up cloths or napkins lose their original function, in order to become incorporated as a repetitive element, lending rhythm and structure to the entire image as in a musical composition. Francesca Gabbiani’s paper assemblages from coloured fragments are woven together to form an image. Her spaces are always ambivalent places which on the one hand appear peaceful and dreamlike and on the other are constructed, strange-looking stages. The atmosphere of the unoccupied and deserted space in Where (2005) is laden with tension and one can imagine the most varying scenes and occurrences that have been carried out in this place.

PARKETT 1.4

Although Rachel Lumsden’s work is clearly representational, the role of the human figure is ambiguous, not least because the artist rarely depicts facial features, thereby avoiding references to narrative or character. The artist’s paintings are too open-ended and ambiguous to be clearly read as narratives; instead they depict charged atmospheric environments, bristling with energy. Her compositions are inspired by a variety of visual sources, from newspaper photos, art historical images and dream pictures to circuit diagrams and advertising material. Combining the overlooked paraphernalia of the everyday with the fantastical and autobiographical fragments with those from the collective unconscious, as in Morley’s Deckchairs (2015).

PARKETT 1.5

In her interior Sailing to Byzantium (2016) Rachel Lumsden brings the past into the present, expressed above all in the atmosphere. The old-fashioned furnishings that appear in many of the interiors – notably an occasional table and ornaments – root the paintings in the mustiness of old-fashioned sitting rooms that remain part of a particular strata in contemporary British society and have a strong tradition in British painting. In Lumsden’s depictions of rooms objects, particularly lamps and furniture, stand in for the figure, while the ambiguity of space is used to heighten the atmosphere. The question of how to deal with effect and reality of the image have occupied Uwe Wittwer since the 1990s. His starting point are the inexhaustible image stocks in the Internet, whose content and truth he appropriates, but subjects to an artistic analysis and re-interpretation. By means of an image editing programme Wittwer re-designs the motifs, crops the formats, changes sections, isolates elements, shifts the colour spectrum or tones it down altogether. He works with mirroring, the reversal of negative and positive and the exaggeration of contrasts, as well as with the alternation between in focus and out of focus areas. In this way the physicality and materiality of his figures appear to dissolve as though they were the echo of a vague memory of something long past. Next to his work is Bruno Meier’s quiet and classic interior, whose colours recall old master styles.

PARKETT 2 KORRIDOR

Kupferstichworte (1991) by Peter Stein in the long vitrine and a selection of lithographs from the cycle Vully I – III (1997) by Martin Ziegelmüller both revolve around the artistic preoccupation with light and shadow, colour and material, as well as time and perception. From 1963 Peter Stein turned increasingly to etching, examining the expression of structures built up from points and lines. The networks create condensed areas and empty spaces, are formed at times in rhythmical cross hatchings and at others in fleeting marks. He presents these drawings with short texts on line, form and temporality, thereby creating a poetic atmosphere. In contrast with these are Ziegelmüller’s strongly coloured lithographs, in which the real is dissolved in sheets of light and veils of fog. Water, clouds and silhouettes of landscapes are hinted at by atmospheric colour gradations, although the recognisable is less significant than the capturing and perception of the unconscious, diffuse and incomprehensible.

PARKETT 2.1

Susan Morris subverts traditional notions of self-portraiture by replacing external ‘appearance’ with recorded traces of everyday activity and automatic, bodily, movement. She has used year planners to track events such as crying jags, sleepless nights or her presence/absence in the studio, transcribing the data to produce abstract screen prints. Interested in the obvious futility of attempts to capture an unconscious, Morris made a series of Plumb Line Drawings using a plumb bob and restricting expression to an absolute minimum. She created a pattern of vertical plumb lines across a large sheet of paper – a process over which the artist had only limited control. The paintings of Rannva Kunoy appear on first sight to consist of a simple, monochromatic surface disrupted by scratch marks that engage with the ghost traces of the frame. Yet on closer inspection the works have a three-dimensional, almost holographic quality. The shimmering colours and shifting forms reinforce the impression that in Kunoy’s paintings something is always just coming into being. A significant feature of Kunoy’s work is the performative aspect. The artist’s movements are clearly recorded in the dynamic line drawings that recall the fleeting pictures traced on frosty windows or with a flashlight in the dark. Anna Barriball’s working method is unusually physical and her experience of time and endurance integral to her drawings and sculptures. The passage of time is perceptible in the lustrous surfaces of her drawings, for which she uses a pencil, paint brush or her fingers to press the paper into the entire surface of the textured object. The relationship between object and surface is a feature of her sculptures for which she wrapped her own body in pen and ink drawings, such as Untitled V (2008). Béatrice Gysin selected this piece as a contrast to a work from a series of sculptural drawings on wood and glass which aim to evoke the spaces of drawings.

PARKETT 2.2

Béatrice Gysin juxtaposes smaller drawings and objects with the 17 heliogravures from Markus Raetz’ portfolio Ombre (2007). The artist meticulously selected existing works from her own archive, in which she found parallels, similarities or affinities with Raetz’ graphic work. Presented as an installation on tables, the combination creates a contrast, however the subject of seeing accompanies both artists, who question in their work the way perception becomes an everyday routine. The result is a quiet, poetic room which invites the viewer’s gaze to sweep over the textures of drawings and hilly alabaster landscapes, to follow the precise lines and discover forms that emerge over and again. The juxtaposition demands intense observation from the viewer for narratives, equivalences or sensuous encounters to open.

PARKETT 2.3

Katrin Hotz encounters the Kunsthaus-Collection with large and small format pen and ink drawings from the period 2011-13. The works in her series Occhi (2013) are formed from net structures and lozenges, empty white spaces or black circles which she develops with quick, rhythmical marks. Her forms break out of the geometrical rigour and recall instead meshwork or organic structures. The artist places these moving forms in a dialogue with Clare Goodwin’s paintings Graham (2013) and Howard (2016). Goodwin contrasts the precise and clearly delineated colour fields with narratives of a social reality by entitling her compositions with names of people. Next to these, in the same room, are abstract works by Heinz-Peter Kohler, which relate unexpectedly with these other paintings and drawings. A contrast in the medium is formed by the video work Am Dach (2017) by Livia di Giovanna which subtly removes the borders between reality, projection and reflection by artfully deconstructing subject matter from her personal environment. The scanning of the architecture with the video camera accentuates the qualities of materials, surfaces, volumes, light, shadow and their relationship to each other.

PARKETT 2.4

In her expressive, fantastical visual worlds, Klodin Erb plumbs the limits of painting and simultaneously questions definitions of gender and identity. The alienation of images from their original contexts and playful interpretations of classical genres, styles and motifs characterise her gestural figurative works. She places less emphasis here on representation as on the process of painting, which should be autonomous and, through brushstrokes and colour, generate the pictorial object as a form of materialisation. Opposite the small painting hangs an even smaller work by Jeanne Jacob. The former student of Klodin Erb evokes in Born in Patriarchy (2020) questions concerning ideals, the relationships between sexes and genders and creates a field of tension between direct and subtle personalisation. She plays humorously with the contradictions and takes as her subject matter here too the way in which the collective can be addressed via the individual.

PARKETT 2.5

Rebecca Horn choreographs in her work movements of people and machines. Although she made performances in her early work, in which she wanted to create body extensions and new experiences of perception with the application of objects, since the 1980s she has made primarily kinetic sculptures that come alive through movement. The artist replaces the active body with a mechanical actor. The mechanised movement of Bleistift-Flügel (1988) can however create poetry with the implied drawing in space. Drawn or intimated lines are always also signs of bodily movements, for which reason the painted traces of a machine can also be understood as the expression of emotions. Katrin Hotz finds in Rebecca Horn’s work a formal relationship with works from her series Pickles(2011-13). These are vague formations of thoughts and gentle structures that stand out against the white background and give the impression of escaping the space of the picture at any moment. Hotz was inspired to make this series during her stay in a Hindu pilgrim place in the North Indian city of Varanasi, where she observed how ripe fruit were dried in the sun. The title Pickles also alludes then to the process of maturing and conserving fruit. Influenced by colours, forms and the exotic surroundings, she reacted to these impressions with black and white abstractions. Jeanne Jacob encounters the winged machine beings of Rebecca Horn very differently. Her figure is caught in an expressive moment of movement and conveys ambivalent emotions. The gaze is directed at the observer and in interaction with the expressive pose, the latter triggers an uncomfortable feeling. The artist plays not only with the ambiguity of body and identity, but also with the expectations of an image. Since the figure directs the gaze onto her opposite, the relationship between the observing and the observed is reversed and the expectations are reflected on the viewer.

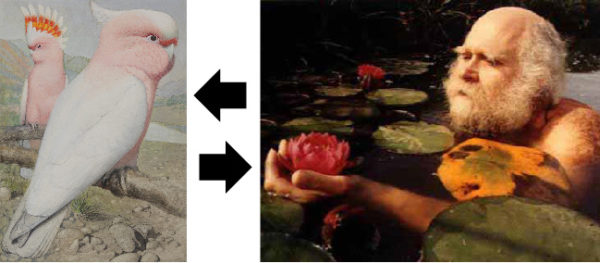

Project Till Velten in the Collections Room and the NMB Neues Museum Biel

As a satellite project the artist Till Velten (b. 1961 in Wuppertal, Germany, lives and works in Zurich and Berlin) presents in the Collections Room of the Kunsthaus his curatorial project TAUSCHEN. A work by Till Velten. In the collaboration with the NMB he created an exchange of works from both collections, which he presents in each case in the other institution. By showing works from the Kunsthaus-Collection in the NMB and vice versa he aims to show how the boundaries between the applied arts housed in the NMB and the so-called free art collected in the Kunsthaus are blurred. From the exchange between the institutions there emerges a changed perspective: it becomes clear how strongly a work is determined by its environment and the perception of viewers. The work is extended by two video interviews with the directors and curators of the two institutions who are confronted with their power to bring works of art out of their sleep in the storage and place them for a certain time in the focus of perception.

Curators of the exhibition

Felicity Lunn, director; Stefanie Gschwend, associate curator Kunsthaus Centre d’art Pasquart

Artists’ talk

Sun 5.7.2020, 14:00 (dt) Béatrice Gysin, Katrin Hotz and Jeanne Jacob in conversation with Felicity Lunn and Stefanie Gschwend.

Guided tours

Wed 8.7.2020, 12:15 (dt/fr) The collection in NMB: On the project TAUSCHEN by Till Velten

Short tour in NMB in the context of Sattsehen

Fri 24.7.2020, 12:15 (dt/fr) Art at noon: Short tour in Kunsthaus

Do 13.8.2020, 18:00 (fr) with Laura Weber, art historian

Followed by a concert

Wed 2.9.2020, 12:15 (dt/fr) The collection in NMB: On the project TAUSCHEN by Till Velten

Short tour in NMB in the context of Sattsehen

Do 3.9.2020, 18:00 (dt) with Felicity Lunn und Stefanie Gschwend, Kuratorinnen der Ausstellung

Followed by videos from the archiv at Filmpodium

Sun 6.9.2020, 15:00 Coffee break with the Kunsthaus team

With complimentary coffee and cake